Day 2 began with a 2 a.m. wake-up call in Portuguese which I responded to with something sort of like “Obrigado” which is Portuguese for thank you. We dressed in our fishing garb–lightweight shirts and zip-off pants pre-treated with insect repellent–and walked the quarter mile to the motel restaurant. There we were confronted with about six tables covered with food, including one oozing with various types of fruit. While eating, we saw two guys wearing lightweight, colorful fishing shirts sort of like ours. We introduced ourselves to Curt and Bobby from Texas and learned they were going on trip with us.

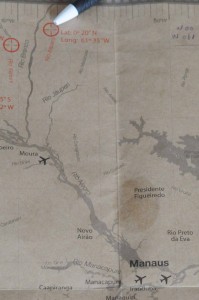

After packing up and paying the $166 reais owed for the previous night’s dinner (about $80 US currency), we met John in the lobby and jumped into a van with Curt, Bobby and four guys from France. John handed out pieces of paper that said something about our upcoming adventure, including that we were en route to the Tapera River. I mentioned that we were told last week via email that we were going to the Itapara River and John explained that they misspelled the river on the map but had made so many copies of the map they didn’t bother changing it. Ergo, the Itapara is also the Tapera. Said river is a tributary of the Rio Blanco, which is a trib of the Rio Negro, which flows into the Amazon River. The Tapera River is really close to the equator.

At the airport, each of our duffels weighed in at exactly the 30-pound limit and I learned that my camera gear does not count towards the weight limit, which means I could have taken my bathing suit bottoms, a pair of sandals, and some other useful things. While packing (and re-packing), the emphasis had been on lures and more lures, so certain sacrifices had been made. Some will prove inconvenient.

Within 10 minutes we were loaded up into a small plane that has both wheels and floats on it.

It holds 8 passengers and their gear uncomfortably.

Once we were in the air, the view out the window gave me the impression that the Amazon and its tributaries go hither and yon all over the country and are surrounded by lots and lots of trees.

After about two hours, we came to what appeared to me to be a pretty narrow stretch of river. The pilot circled the area once, circled again lower . . .

. . . and landed us safely on the Itapara /Tapera River. Waiting on the banks to go home were several Americans–all men. Waiting in boats to take us to our cabins were our fishing guides–all men.

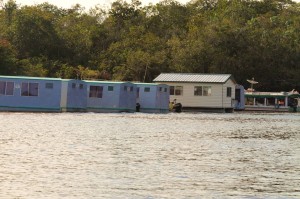

The guides loaded up our luggage and motored us to our floating cabins. The first thing I noticed is that the floating cabins were beached on a sand bar so weren’t entirely floating. In fact, we would never be on the floating cabins when they were all floated down the river. We would be staying on beached, semi-floating cabins. And that was just fine with me.

Our cabin looked like this from the outside.

The inside of our cabin looked like this. The first thing I noticed: two twin beds. How romantic.

Unpacking meant putting some stuff on a single shelving unit and other stuff on a table. It also meant adjusting the air conditioner to cool things off a bit more. Afterwards, we wandered to the air conditioned dining cabin to get some bottled water and make a lunch. There we met Bibi, the camp host who made us feel immediately welcome. She said we could make a lunch and go fishing whenever we were ready. She also said to bring our flashlights to dinner because, “The caiman sometimes like to sleep on the camp beach at night.” Hm.

I made a cheese sandwich for myself, a ham and cheese for Mark, and we loaded up our gear into our guide’s boat. His name is Prato and he’s a 34-year-old Brazilian who doesn’t speak much English.

Mark had practiced Portuguese using some DVDs over the last month and he was quite excited to chat with Prato and expand his grasp of the language. That was good because all Prato said was “Bom dia” (which means “good day”), followed by “We go” as he waved towards the boat.

As we motored down the river, I spotted my first bird, which I later identified as a pied lapwing.

About a half mile downstream from camp was a sight that made me gulp.

The caiman was about 15 feet long. And while it was currently dead, it wasn’t dead before and that meant it was formerly roaming the waters near our camp. And it maybe had big friends. It being big and dead also meant something really big had killed it. Bibi later told us that a jaguar had killed the big caiman. To summarize, we knew caiman got big, caiman liked to hang out at our camp sometimes, and jaguars like to eat caiman. Hm.

Downstream a bit further, we came across a jabiru stork.

About twenty minutes later, we got to a spot Prato said was good for fishing and we knew that because he stopped the boat and said, “We fish.” Now, the great thing about having a fishing guide is that he is perfectly happy to tie a lure onto a fishing pole and he’s perfectly happy to take the fish off the hook, too. Prato looked through Mark’s fishing lures, selected a jig for me and something else for Mark and we were off and fishing. Soon I was distracted by a giant river otter. I didn’t get much of a shot of it, but enough to show that I actually saw a giant river otter on the Amazon!

Shortly after we saw the river otter, something made a large splash near Mark’s lure. It was such a large splash it caused both Mark and me to stop reeling in our lures. Prato said, “Reel!” so Mark continued reeling and wham! the peacock slammed his Yo-Zuri crystal minnow. He set the hook and reeled in his first peacock bass. We were both very excited. Here we were two sort of ordinary people from Michigan on a tributary of the Amazon River catching peacock bass. Cool!

Later, Mark caught a butterfly peacock bass, which looks like this.

The action of our fish caught the attention of this caiman. He loitered around for a few minutes, realized he was in the company of inexperienced gringos who were unlikely to catch too many fish for him, and disappeared in the water.

We moved to a different spot after Prato said, “Moving!” and I caught this wolf fish, or traira.

Mark also caught this toothy fish, which is a dog fish. Some call this a mini barracuda.

I caught a couple of peacock bass but they were pretty puny. I kept getting distracted by birds, including one that was really hard to see.

This colorful bird was a lot easier to see.

This hawk didn’t seem to mind us getting fairly close.

And finally, we saw this bird. It’s called a southern lapwing, which is odd because I was just minutes north of the equator when I saw it.

We found this bird to be most peculiar because when we zoomed in, we noticed it had two red protrusions on its chest. My birding pal, Mike Bishop, Alma College, later told us that these are “bone spurs that are protruding from the wrist of the wing. Both males and females have them and I assume they are used for defense, maybe.” Strange indeed.

At around 4:30, Prato took us back to camp where Bibi greeted us with a notepad and paper to document what we had caught. Prato reported that we’d caught 8 peacock bass. Bibi wrote that down, nodded and told us that snacks and cold beer were waiting for us in the dining cabin.

The floating dining room had a refrigerator with lots of cold beer. The room also contained a small bar allowing us to make a rum and Coke. Some kindly staff person had also mixed a lime-based drink that was really, really easy to sip. And so I did.

We’d just sat down with a cold drink when Roberto, one of the camp staff, came in with a small stick in his hand and started beating on a small snake that had made the mistake of coming inside the dining cabin. Mark jumped up from his chair, tried to tell Roberto not to hurt the little snake, that it was harmless. Now, how he knew the snake is harmless is beyond me, but before I could say anything, Mark had the snake by the back of the head, had carried it outside and thrown it into the river. When I asked him what kind of snake it was he said, “Clearly, since it’s now in the water, it’s a water snake.”

With that, dinner was served. It started with a very tasty bowl of soup, offered with a dash of a container of farina that was always on the table. Soup was followed by a variety of food including fish, chicken and beef dishes, the extent to which surprised me considering we were out in the middle of nowhere. It was all quite tasty.

During dinner we learned that Bibi radios in every evening to report on the fishing, and what she reports is the number of peacock bass caught by the guests and the number of peacocks 8 pounds or bigger. Nobody seemed to care about wolf fish, dog fish or any other fish. And nobody talked about birds. It was all quite peacock-y.

Night fell by the time dinner was over. And because Mark and I had forgotten our flashlights, Bobby kindly walked us safely back to our cabin. I wrote a few notes in my journal, waved goodnight to Mark from my twin bed, and tried to nod off without thinking too much about snakes and caiman.

Hello Amy,

My name is Fulvio, I have special interest in biology and nature, especially I am fascinated by jaguars and I would like to ask you about the picture you took of the dead caiman above. Could you please confirm that this caiman was killed by a jaguar? From the picture I estimate this to be a “black caiman” and a large specimen, as you state, around 15 feet (4.5 mt). This would be a serious report of a jaguar killing large caimans when they are forced to do it. Most scientists believe that jaguars only prey the “smaller” spectacled caiman, and that a large black caiman would be beyond their strength and capability. Few scientists however, think that the jaguar is simply very selective and cautious when choosing prey, and will attack such a large foe only when very hungry and there is no other easier available prey around.

I can see on the caiman’s belly some scratch signs probably made by the jaguar’s claws, and also the chew marks on the tail look as made by a feline creature.

Thanks for your reply, it would help me in my study of the jaguar, this secretly and majestic cat.

I am not so sure that the caiman might be 15 feet, that’s extremely ,extremely rare that they get that big, anything over 4m would be very large for a black caiman.

Also if there any evidence it was an old or sick caiman?