Sunday, August 28, 2022. By our third day in the jungle I hardly noticed the rooster in the morning and was up before the alarm, excited about whatever the day had to offer. What this morning had to offer is something I didn’t get a photo of, which was one of the guides pounding on some leaves in a Ziplock bag and sharing something from the bag with several of the other guides. Memo said they were sharing cocaine leaves and that it’s legal in Bolivia to do what they were doing. I had noticed our guides sometimes had something stuffed in their cheeks but hadn’t thought anything of it. While I felt very naive, Mark said he’d like to try some cocaine. I suggested that perhaps that wasn’t the best idea since he was not exactly young and because it would take up to four hours to get him to the nearest hospital if things didn’t work out. Thankfully, he opted against.

That’s how the morning started.

We headed down the river with the rising sun, following the other two boats. This video shows some of what we went by.

After we had fished for a while with nothing to show for ourselves, we saw this wattled jacana take a bath. It was a perfect place to throw a lure for a peacock bass–near some weeds, by the shore–but we let him bathe before we threw anything.

The jacana made quite a bit of a splash, which I thought would attract predators.

Afterwards, it spread its wings and wattled–I mean waddled–to the safety of the shore.

In fact, the morning was more bird-like than fishy, but most of the birds flew off before I could get a decent photo of them, like the two birds on the left (pinnated bittern and juvenile tricolored heron, I believe). The bird above is a juvenile anhinga.

This is a capped heron, which I had seen before but only when the sun had set and I was literally shooting in the dark. I love the colors on this heron.

We saw these blue and yellow macaws postering for position in the crook of a tree.

It was late morning when we finally got into some peacock bass. I will note here that while I was interested in each fish Mark caught, he was a bit busy when it came to taking photos of me with fish, hence a shout out to Bismark for taking some photos of me.

Seriously, one thing I love about Mark is how he is laser-focused when he’s fishing.

We caught a lot of peacocks at one spot. The fish shown here would turn out to be one of Mark’s biggest peacocks and about as big as this species gets in this part of the Amazon.

On another stretch of river we saw this pied plover, also called a pied lapwing. Or it’s a pied lapwing, also called a pied plover. See, per Wikipedia, “Historically, the pied plover was considered to be a plover, which is a bird part of the subfamily Charadriinae. Most recently, it has been moved to the subfamily Vanellinae, which are the lapwings.” Add this to the list of things to take up with the bird namers.

These are black skimmers. Their upper beaks are shorter than the lower beaks and they fly with their mouths open, skimming across the water, the lower beak acting as plows on the water to catch fish.

This is a solitary sandpiper, which was all by itself, so, well named. I have seen these in Michigan now and again. They overwinter in Central and South America.

For lunch we pulled off the river and climbed up a small hill to this beautiful spot, which was raked and kept tidy by the guides. They carried the coolers up the hill and we enjoyed an ice-cold beer while they started a fire and gutted some fish we’d caught, including one of my peacock basses.

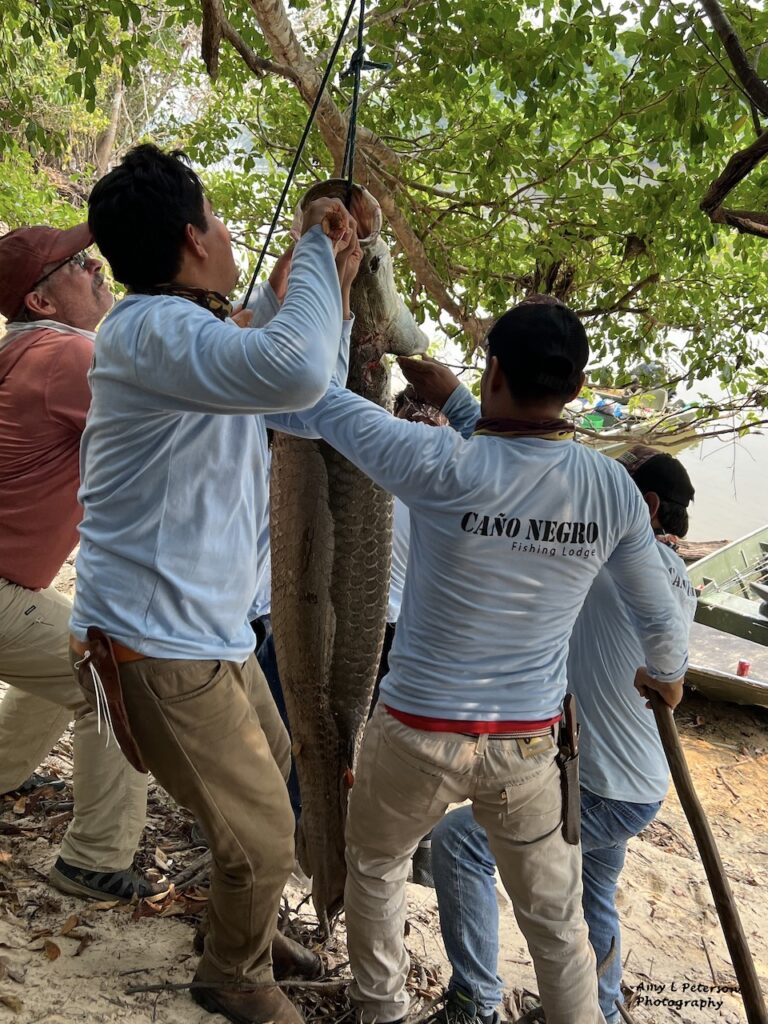

Before a fire was started, though, the guides had to deal with Drew’s arapaima, which oozed up both sides of the bottom of the boat.

This massive arapaima had a 41-inch girth and its length had to be measured in sections because it exceeded the maximum length of the tape (60 inches).

And yes, I took a measuring tape to the jungle, primarily to measure catfish…which I never measured because we always were in a hurry to release them.

With the big fish hung up, the guys used pliers to remove some scales. Scales can be dried (but usually use their color), and if left to dry under something flat and heavy–like a tackle box–the scales will remain flat. If left outside in the open air ended up with curled scales. Mark was a seasoned scale smasher, so our scales were nice and flat when they dried. Apparently, some people paint arapaima scales and sell them as art work.

After a beer, it was time for a nap in the hammocks the guides had strung up for us.

While we all napped in hammocks and listened to the wind and an occasional bird calling from the woods, the guides cooked fish over an open fire. They brought the cooked fish over and we forked out what we wanted. We also each got our own plastic container with several dividers: one with rice, one with corn mixed with peppers, and one with a tiny potato.

And yes, this selfie will go down as one of the worst ever.

After lunch we napped a while longer, and at around 3:00 we fished nearby. We saw lots of fish, but our lures were of interest to only a few fish.

We did see this bird, which is a gray cowled wood rail, a first for me. It lives in central and South America. I was intrigued by the black feathers sticking out of its back–they apparently wiggle that when they’re strutting along.

Way up in a tree I saw these birds, which I believe are chestnut-fronted macaws. Amongst the questions I found online about these birds was a question about how much they cost. It’s a strange thing, seeing these birds in the wild and learning people have them as pets.

As we headed to another stretch of river, we passed the spot where we’d had lunch. And there, lying in the water unceremoniously, was Drew’s giant arapaima. Black vultures had gathered but were unable to penetrate the scales with their sharp beaks.

The rest of the afternoon was slow fishing for us and rather frustrating.

The sun set, cat fishing started, and by 6:30 or so Mark had pulled in the giant red-tail catfish to the right. At around 7:15 he pulled in the one, below. I think the fish picked up my frustration vibes, because they completely ignored the chunk of meat on the end of my line.

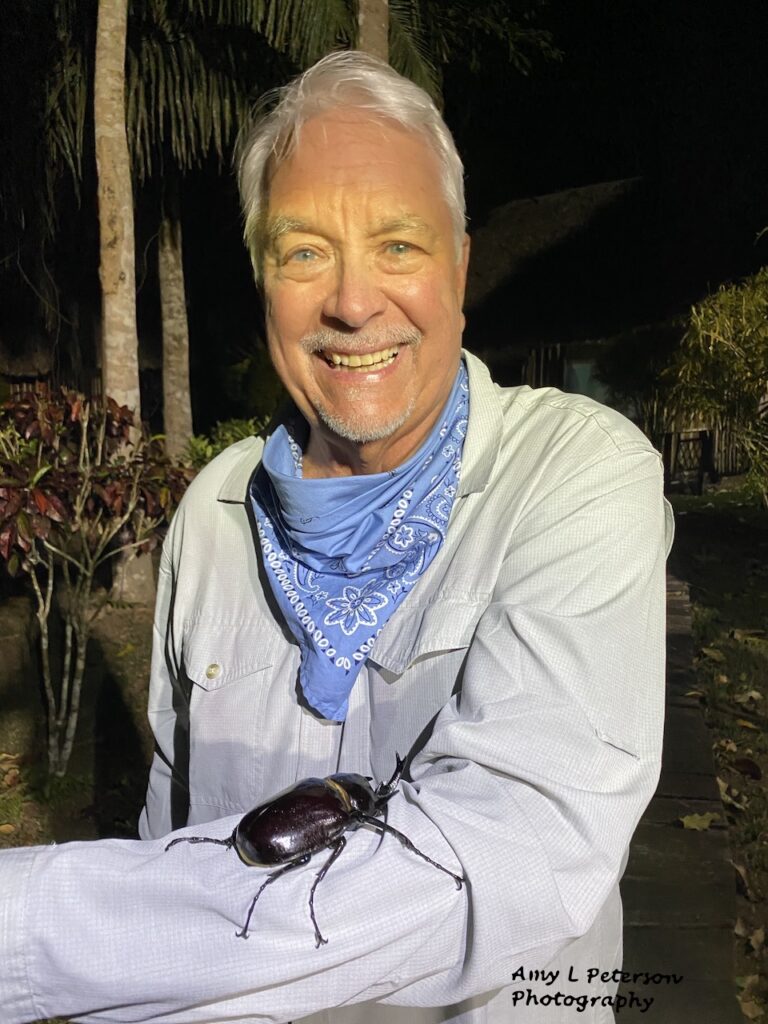

When we got back to camp, I swung through the lodge to grab a beer, and Mark went on to our bungalow without me. On my way back to our bungalow, I stopped when I saw this, a giant rhinoceros beetle on the boardwalk. I snapped this photo, told Mark what I’d seen, and he came running back out with a flashlight.

Mark had spent a couple of months in the jungle of Costa Rica back in the 1980s, and we had gone to Costa Rica last year, and to the Amazon twice before, yet this was the largest rhinoceros beetle we had ever seen. Mark was like a kid at show-and-tell, picking the beetle up, carrying it inside the lodge, showing it to our friends from Maine, Memo, and the cook staff. Afterwards, he took his pal to a palm tree and carefully released it to the tree. Mark said male rhino beetles will fight over females, and it’s possible his pal lost a fight for a female up in the palm tree. By releasing it, he felt he was giving his pal a second chance with a female. He told the beetle to “Go get a babe,” as he walked away.

This video shows the beetle right after it was released. This video shows it working its way up the palm tree, which was trickier than one might think.

As we walked back to our bungalow, Mark said catching his first arapaima and interacting with the largest male rhinoceros was amazing. I went to bed happy because Mark was so happy.