Friday, August 25, 2022. Having immersed ourselves in Bolivian culture and relaxed for a few hours at what will go down as one of my favorite motels–the Los Tajibos–we rose early in the morning on August 26…so early, we didn’t get breakfast. And darn, did it smell good as we trotted by the dining room. We checked out of our room and hung out in the lobby of the motel for several minutes before I happened to reach out for my arm, went, “Poo!” ran to the desk, got a key, ran back to our room, and retrieved my watch from the bathroom counter.

Benjo arrived a few minutes later and drove us through town to a small airport where a half dozen hapless roosters were bound and gagged, lying on the floor, the sight of which about made me barf. Benjo’s brother was standing nearby and explained that cock fights are big in certain Bolivian circles, and wherever these cocks were going there would be lots of money to win or lose–like a $30K bet was not out of the question. He also said that a cock fight lasts 45 minutes and any survivors get treated and taken care of…so they can fight another day…to the death. It’s a part of the culture, he said.

As he talked I gritted my teeth and nodded like a stroke victim. It took everything I had to not release those roosters.

It was equally hard to photograph fighting cocks en route to their private airplane, and for some, an almost certain death.

I walked about for a while, because it turns out that the Bolivian government requires a pilot to get permission from the government to put gasoline in his/her airplane. So we waited. And waited. An hour later, we got to pose in front of a little red and white plane that would carry us to the Cano Negro Lodge.

My stomach churned for a while after the roosters were carried away. In fact, when Benjo offered to buy us a bagel from a tiny little stand at the airport I said thanks, but no thanks, because I was not hungry. Instead, I walked about the tiny airport, did a word puzzle on my phone and stepped outside to look for birds. Like wild birds that could fly.

Before we left, a nice pup sniffed our big bags for drugs…and perhaps roosters. Finding none, we were free to go.

After the luggage was loaded up and secured with ropes or bungee cords, Mark was belted into a seat, while I assumed the co-pilot role, which I know nothing about.

Not too far into the two-hour flight in our small plane, the pilot placed these sun deflectors on the windshield, making me realize that one does not need to see out the front when one is flying. Gulp.

Meanwhile, unable to find any cup holders, I held a small water bottle “with gas” (meaning Co2) between my legs, which was a good idea until the bottle suddenly went “Psssssed” between my legs. That about made me pee my pants.

So here’s a tip: don’t fly with water bottles containing gas between your legs.

While flying, I took this photo and was relieved to know where the exit was…several thousand feet in the air.

I noted that traffic circles are a thing in Bolivia.

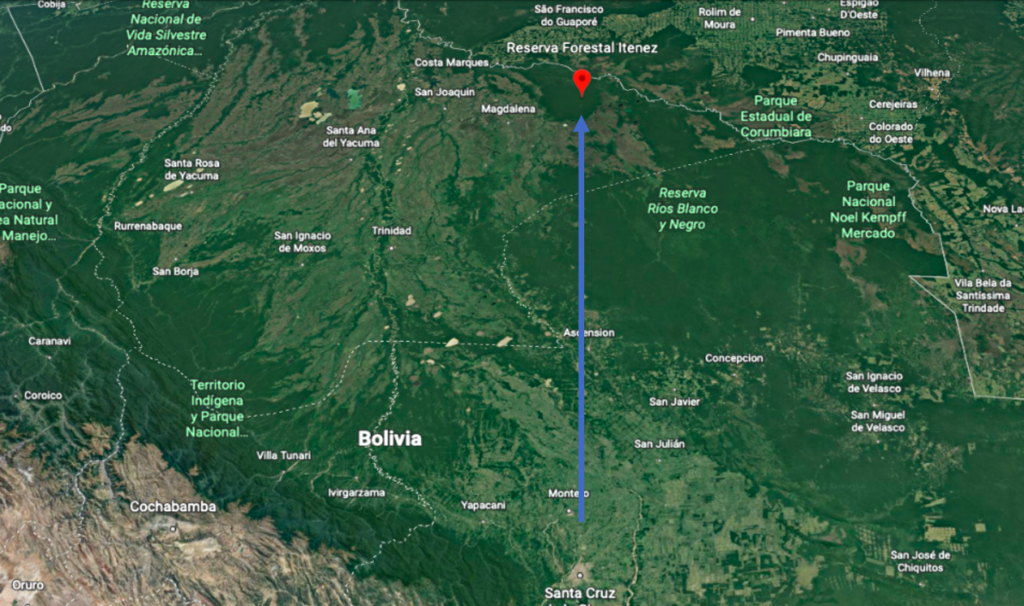

The Cano Negro Fishing Lodge is on the Itenez River, which is a tributary to the Amazon River. We would be fishing both the Itenez and the Rio Negro. Note also that to the right of the red balloon thingy on the map is a wiggly line denoting the boundary between Bolivia and Brazil.

About two hours after we took off, we saw this river at low altitude, which I guessed was near the lodge. Happily, the sun blockers came off the front window of the plane and the pilot landed us safely on a dirt landing strip using all available windows.

While we got some ice-cold water from a cooler and posed for photos, Cano Negro Fishing Lodge staff unloaded our luggage onto a wheeled cart and pushed it down a manicured trail. We met Jessica, a wonderful young woman who had learned English while on the job at the lodge and whose home is four hours away, by boat.

This is the lounge near the bar.

This is the bar.

A

As we settled in for a ride down the Rio Negro, Memo–who runs the lodge and makes sure everyone who comes and goes not only survives, but catches fish–went over the game plan with the guides in Spanish. That’s Memo to the far right in the photo. He’s actually much bigger in real life.

We also met the Morrises: John Jr., above, with his guides, and, to the right is Drew and dad, John Sr., who is 83. They were super nice guys from Maine. They are also actually bigger in real life.

Now, I knew we were going to be fishing in a preserve, but I never thought we’d see a jaguar, let alone one sitting in the sun as if posing for a photo. Two other jaguars were hiding in the vegetation nearby, which in all likelihood were this young jaguar’s parents. I had to pinch myself. Here I was, a woman from Michigan, taking a photo of a jaguar in Bolivia!

My last photo was of our jaguar pal walking away. This shot isn’t great but it might give a better sense of the jaguar’s size.

We continued down the river and had just gotten our lures in the water to try to catch some peacock bass when I saw this Hoatzin, which is pronounced “watt-sin,” with an accent on the “watt.” Mark had seen this bird in Ecuador many years prior but I had never seen one and knew little about them. It turns out these are the only birds in the world that have a foregut and crop to digest their food rather than a stomach. The foregut has lots of bacteria to break down the food, which gives these birds bad breath, and apparently the reason their nickname is stink bird. I liked their punk hairdo.

We started fishing by throwing plastic lures. The first fish we caught was a bicuda (pronounced “bye-coo-da” with an accent on the “coo”). According to a site called Kidadl.com, bicuda can get up to 34.6 inches and weigh up to 13.2 pounds. This one was definitely on the puny size, but it sure looked ferocious. Bizmark handled and released this feisty little fish.

The next fish to the boat was this red-bellied piranha. We’ll just ignore the fact that the red looks more orange. These fish have amazing teeth and have to be held properly to avoid super sharp teeth combined with a super powerful chomp. I “let” Bizmark hold and release this fish, too.

Mark’s next catch was a jacunda. We’d caught a couple of these on a previous trip to the Amazon, but this was bigger than most. Check out the long dorsal fin and the black spot. I also noted that it lacked the thick scales of most Amazon fish.

My next fish was a peacock bass. While fighting this one, my rod broke, which was somehow fitting since I’d broken a rod on a previous trip to the Amazon. The thing about a broken rod is that if ya keep on reeling, the fish comes to the boat just the same…along with the broken piece of the rod.

This fish was somewhere around 3.5 pounds. I love its color–the bright orange, yellow on the bellow, black lines, the black and yellow spot.

For those who don’t fish–the thing in my hand is a Boga Grip, which is a gadget that allows people to hold fish safely. When I held the fish over the side the boat and lifted up on the black part, the metal jaws parted and the fish disappeared back into the water.

I’ll also note that the rod I have is a bass fishing rod.

These dolphins are found throughout the Amazon river but considered vulnerable in some areas. We had seen pink river dolphins in Brazil, and there, they went after the one and two-pound peacock bass we released. The dolphins we saw in Bolivia were in small groups and worked together to catch fish. They didn’t seem interested in ours.

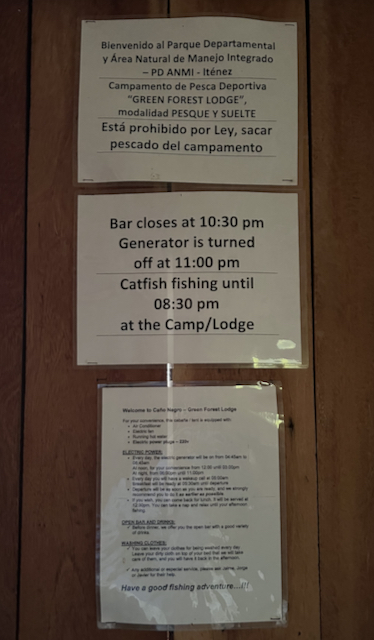

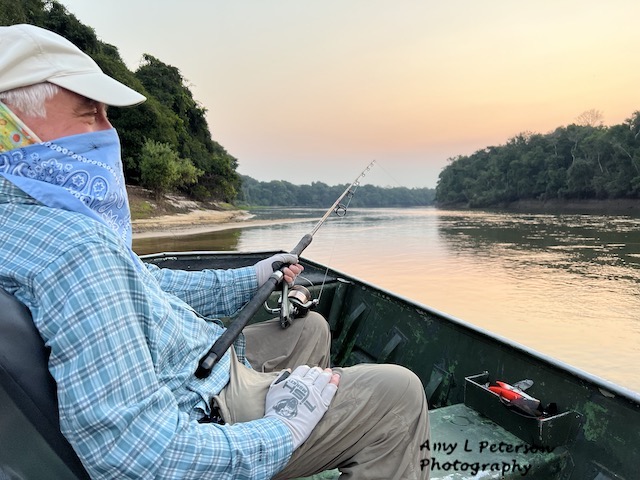

We saw the pink river dolphin at 5:15 p.m.. The sun had started to go low on the horizon. Our guides moved the boat to another stretch of river, attached chunks of fish to the end of fishing rods much heavier than bass rods, handed one rod to Mark, one to me. They said we were cat fishing. (Yup–we’d walked right past that sign in our bungalow.)

It was then it occurred to me that we’d be fishing in the dark.

There was a sunset on this, the first day, but I didn’t take a photo because I was a little distracted about the idea that it was quickly getting dark. And soon it was pitch black. There were no stars, no moon.

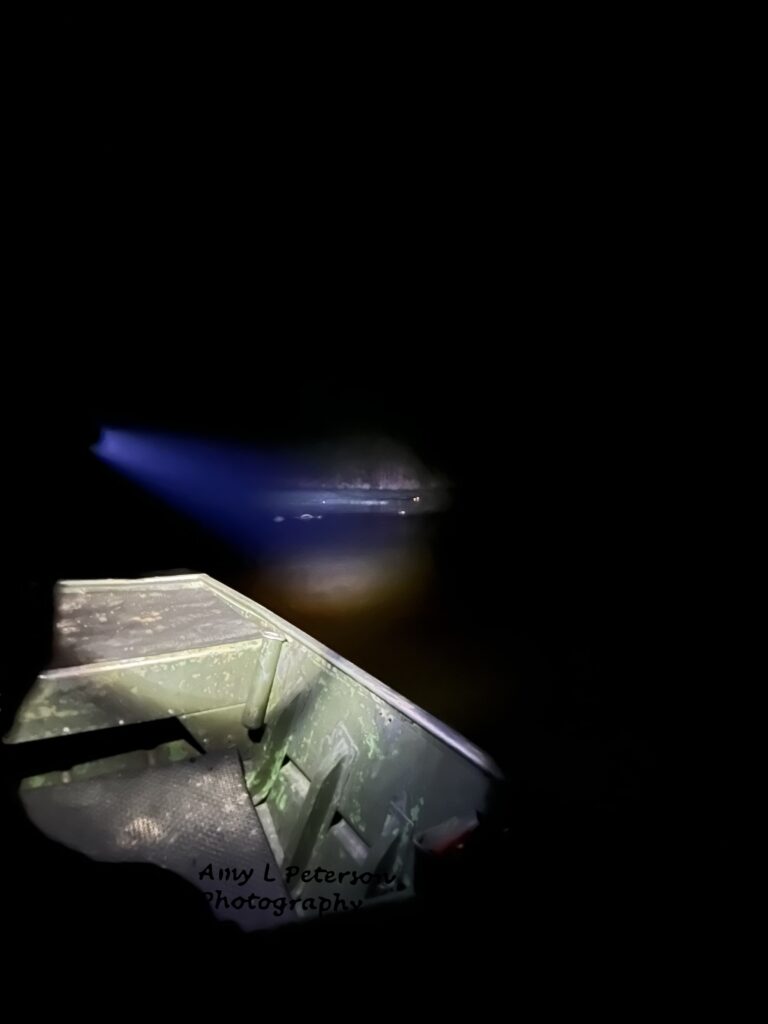

So, imagine sitting in pure blackness, holding a heavy rod and waiting for some fish--some fish you’ve never seen before but you know is going to be big–to hit your baited hook. Imagine your guide only occasionally shining their flashlight nearby, and when they do, you see nothing but caiman–caiman on the shore far away and close by, and the red of caiman eyes everywhere the light shines in the water.

Occasionally, you see bats skimming across the water–some small, some–the fish-eating bats–larger. They are after insects, which you also see in the light, none of which want to eat you. The guide shuts off the flashlight and you’re in the pitch black again, waiting. And while you wait, you hear the “work, work, work” of frogs, mixed in with the pleasant sound of bowling balls being dropped in the water, sometimes far aways, sometimes close by, as caiman launch after prey.

It was terrifying, thrilling, fun, scary, and incredible. Between the loud splashes, we heard the sound of birds calling that we’d never heard before, the steady sound of “work, work, work” as frogs called from all around us, and the occasional giggle from Bizmark, chatting quietly with Raul.

For two summers when I was in college I got to go salmon fishing on Lake Michigan before work. We’d leave before daylight and watched the sun come up to the zzzzzzz sound of line stripping off a reel when fish hit. Fishing for giant catfish in Bolivia was similar as far as the zzzzzz went, but nothing else was the same–in Lake Michigan I wasn’t afraid of anything in the water; in Bolivia, everything had sharp teeth and was trying to eat everything else. And I had a one in four chance of being chosen by a huge caiman if it came out of the water and tried to nab one of us. The noises were very different, and the sun was not coming up anytime soon.

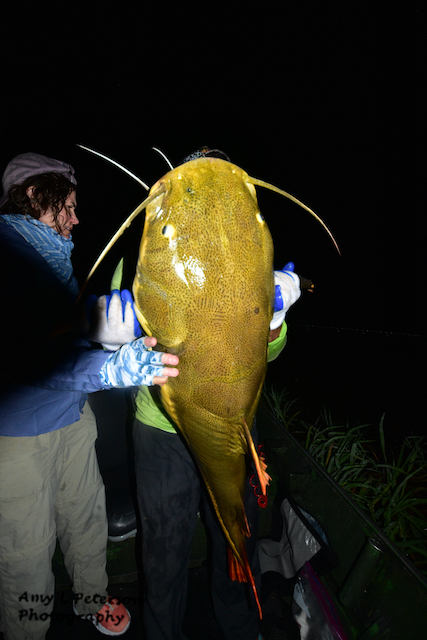

Finally, my first redtail catfish came to the side of the boat, and I saw its huge head and heard it grunt, and heard Raul grunt as he lifted it out of the water…I was in awe.

In the photo, the blob to the right of the fish’s eye is the chunk of meat used as bait.

This was my first redtail catfish and it probably weighed upwards of 90 pounds. Raul would not let me hold it, likely because he didn’t think I was strong enough and probably afraid I would drop it in the bottom of the boat and hurt it, which I did not want to do. I loved that this fish had the shape of a giant, golden tadpole, how it was nearly as big as me, how it touched me in the face with its big whiskers. Its grunting made me want to release it quickly.

Raul did slow down when the river got really narrow, and that’s when Mark and I got see what the shoreline looked like at night.

But as soon as the river got wide again, Raul opened up the motor and we were off at full speed again. I was quite relieved to return to the lodge safely.

We had no option but to trust that Raul knew the river like the back of his hand, because he drove the boat at full throttle most of the time…and some of it in complete darkness. While Raul zigged and zagged down the river and Bismark shined his flashlight when they found it necessary, Mark and I spent most of the ride with our heads down so as not to get bugs in our eyes. I imagined the boat hitting a log at full speed, flying out of the boat and into the water, and getting munched by a caiman. I mouthed to Mark that I loved him.

We arrived at the lodge with a “Yay!”, shared the news of the day’s catch with Memo, said goodnight to our guides, walked quickly up the hill to our room and used the bathroom and went “Yay!” again.

We returned to the lodge to swap stories with our new friends over a light dinner and beer. Before we sat down, though, we had to let this tree frog know that what we were having for dinner was probably not going to be to his liking. Drew carried it outside and let it go.

It was 9 p.m. when we were done with dinner. It had been an absolutely incredible day.